Have you ever been to an IKEA store? Then you are perhaps already familiar with the satisfying effect of assembling and building stuff yourself. The IKEA effect has been investigated extensively in behavioral and decision sciences. But what does it tell us, and how does it help us with better cybersecurity investment decisions in the long term? What can we learn from the IKEA effect, and how does it help us sharpen our minds while crafting cybersecurity as an organizational function?

IKEA effect explained

Buying furniture from IKEA tends to save us on pricing and transportation (almost all parts are stored and transported flat). But the most significant psychological value is that “labor leads to love.” Daniel Moshon examined the IKEA effect: “The increased valuation that people have for self-assembled products compared to objectively similar products which they did not assemble.”

Moshon’s paper describes possible consequences of the Ikea-effect in corporate environments: “The self-overvaluation that occurs as a result of the IKEA effect has implications for organizations more broadly, as a contributor to two key organizational pitfalls: sunk cost effects, which can cause managers to continue to devote resources to failing projects in which they have previously invested and the “not invented here” syndrome, in which managers refuse to use perfectly good ideas developed elsewhere in favor of own ideas.

The shift of focus: Outsourcing

So how can we use the IKEA effect as a learning opportunity in regards to cybersecurity? Let’s have a look at how businesses procure cybersecurity. Nowadays, companies increasingly tend to issue Request for Information or Proposals concerning outsourcing their security function or specific services. Nothing wrong with that, but they tend to forget this requires clarity on the demand-supply relationship. We’re talking responsibility and accountability, not only during Business As Usual (BAU) but precisely when the “shit hits the fan.” What can we expect from the supplier? And what can they expect from ourselves, and are we able to live up to that urgent demand when you least expect it? By the way, this is when CISOs are put to the (stress)test.

We observe the following pitfalls that are related to the IKEA effect during RFI and RFP processes

- From Activity to Outcome: Organizations request RFP and RFI activities rather than measurable outcomes; they tend to focus on requests, for example, buying a SIEM or SOC services, where traditional SIEM solutions do not cover the future need. In this example, traditional SIEM solutions create tunnel vision, tend to look back, alert us “after the bang,” and are static since they rely on predefined use cases from things we already know. In other words, they generate noise which causes decision latency. Some RFPs and RFI’s request to describe how these SIEM services should be assembled rather than what is expected of them.

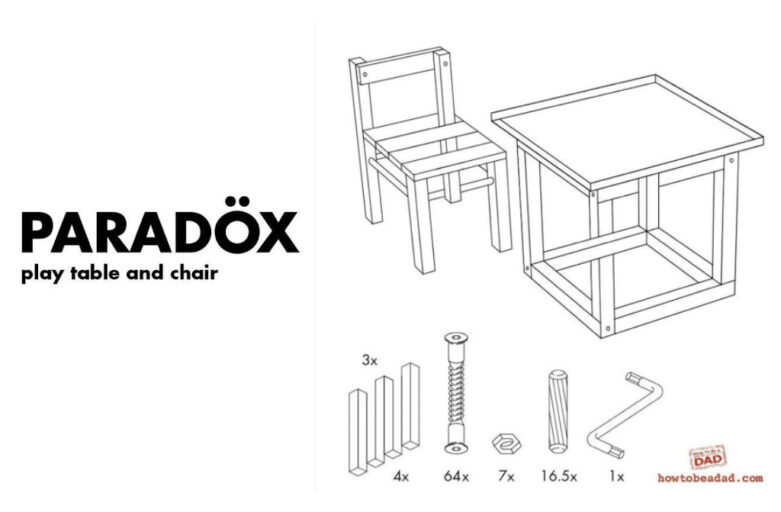

- Describe over Prescribe: Organizations tend to prescribe -like an IKEA manual- what they want rather than describing Why they need it and How they want it. The Why is essential as the rationale of decisions. In the earlier example, it is crucial that if an organization pursues an M&A strategy, easy onboarding of these new acquisitions is vital. The How is important since this defines the form of the Outcome. For example, if the requested outcome for Mean Time to Detect (MTD) is less than one hour, I want the supplier to interplay with me to achieve this, and then the How becomes a leading principle. So How the supplier delivers the service to support my strategic goals is essential, and that’s where I want to have my periodic service level agreements and conversations, rather than a manual. This requires a mindset of relying on others to know what is best for you. This CISO-orchestrating-mindset is what we describe in previous blogs.

- Delegation means letting go: This is hard for many people, and we experience this in our practice. Security professionals are dying to develop and run security themselves and force their hobbyhorses upon -competent- suppliers. They tend to forget that their organization’s objective is not to build and run a security function alone. Their boss usually wants to outsource since they understand that building a 24/7 “craftmanship” with an eagle eye department comes at a price.

Managers with business management or economic background tend to be more aware of their own organizations’ “not invented here” syndrome. This is confirmed by Wakefield Research and Deloitte, why half of the C-Suite execs want to outsource their security operationsand get more ‘bang for their buck’[1]. Thus, opening up to more outcome-driven results that are measurable and, therefore, better expressed in a price. It simply makes more sense to consume security services with a clear outcome, such as Mean Time to Detect (MTD) or Mean Time to Resolve (MTR), than the number of log megabytes or firewall throughput. Due to their price elasticity, these old-school metrics contribute to the seller rather than the buyer. Pricing models from SaaS providers charging for additional security services on top of their SaaS services are not uncommon but perverse since security should be an inherent part of the offering. I’m not surcharged for airbags in my car, right? We discuss these perverse models in this blog.

Decision-making process

The message here is simple: before companies embark on a security journey of outsourcing, issuing out RFPs or RFI’s, they should challenge themselves on:

- Are we able to build and run the security function ourselves? And to what extent? Are we competent enough, and can we objectively assess the outcome and efficiency?

- Do we aim to lower our Operational Expenses (OPEX) on security in the long term? Do we have a – resource-investment scenario behind our cybersecurity plans with alternatives? Challenge and discuss the “sunk cost effect.” Assess already made investments and see how to leverage those rather than buying new stuff one hand, or write off the sunk cost and start with a better solution.

- Did we rigorously scrutinize our running projects and do they contribute to a better outcome, such as MTD, MTR, etc? To avoid the “not invented here syndrome.”

My general advisory here would be to develop a pre-mortem analysis where together with supplier and internal stakeholders, two scenarios are created in the form of a story; one with a positive outcome and one with a negative effect.

Organizations that conduct pre-mortems tend to make better long-term decisions since they share common interests, outcomes, and expectations. Pre-mortems are done via stories and must be done under professional and objective guidance.

We would also suggest working with Best Value Propositions rather than prescriptive RFI or RFPs. A value proposition is a statement that identifies clear, measurable, and verifiable benefits consumers get when buying a particular product or service. It should convince consumers based on verifiable propositions that this product or service is better than others, adds value, and contributes to solving the problem(s).

We like IKEA’s concept of building and assembling your furniture, but it becomes another ball game if you want to buy a large closet with mirrors, sliding doors, and lighting. Those are the moments when my better half “objectively” advises to leave that up to the specialists. And wecould not agree more.

In Cybersecurity, we tend to perceive ourselves as experts and know everything. In most cases, you cannot know everything, and the higher you come in the leadership food chain, you need to rely on others and delegate to get the best results. For some security leaders, that capability requires investing in delegation, understanding future roles and acquire the right talent. And financial capabilities to understand where we gain more value for money; doing it ourself or outsource.

Used Sources

[1] M. Norton, D. Mochon and D. Ariely, The “IKEA Effect”: When Labor Leads to Love, Harvard Business School, 2011.

[2] Y. Bobbert and J. Scheerder, “On the Design and Engineering of a Zero Trust Security Artefact,” in Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Vancouver, 2021.

[3] Y. Bobbert, J. Scheerder and T. Timmermans, “Perspectives from 50+ years practical Zero Trust experience and learnings on buyer expectations and industry promises,” in SAI Conference, London, 2022.

[4] Y. Bobbert, “Which of these 4 CISO archetypes do you deserve?,” Antwerp Management School, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://blog.antwerpmanagementschool.be/en/which-of-these-4-ciso-archetypes-do-you-deserve.

[5] Y. Bobbert and M. Butterhoff, Leading Digital Security; 12 ways to combat the silent enemy, Utrecht: https://12ways.net/blogs/emerging-roles-in-digital-security/, 2020.

[6] Wakefield Research and Deloitte Report on The future of cyber survey 2019, polled 500 C-level executives who oversee cybersecurity at companies with at least $500 million in annual revenue including 100 CISOs, 100 CSOs, 100 CTOs, 100 CIOs, and 100 CROs