Over the years we learned that other management models outside the digital security profession are relevant for digital security. In the coming three blogs, we will present three examples of management models pertaining to Digital Security. This is the first of this trilogy.

Introduction

Hackers and negative (social) media hypes have proven able to bring proud organizations to their knees, yet many information security managers and CISO’s lack a strategy to anticipate and overcome such unpredictable challenges. A survey conducted among key people in the digital security field reveals how perilously far behind their strategic thinking has fallen and what managers and board members can do to catch up. In this article we show how management models can help with defining the right security strategy. Harvard professor Michael Porter’s Five Forces model is an example of a management instrument that can assist business leaders in making strategic plans and reveal knowledge on why certain forces must be controlled and others need not.

At the Infosec Dialogue in London (UK) on October 4, 2015 we polled 30 CISOs on their acquaintance with Michael Porter’s Five Forces model. None were familiar with the model. Below we demonstrate how this model can help to identify relevant threats, actors and forces that shape a strategy but, above all, how Porter’s model can be used to close the language gap between IT nerds and people on the Board.

Situational Awareness

Forty-one experienced security managers and officers, all of whom have worked for 10 years or more in the field, were asked a range of questions about the forces they deal with when formulating their security strategy. This research was conducted with Antwerp management master students and published in 2018[1]

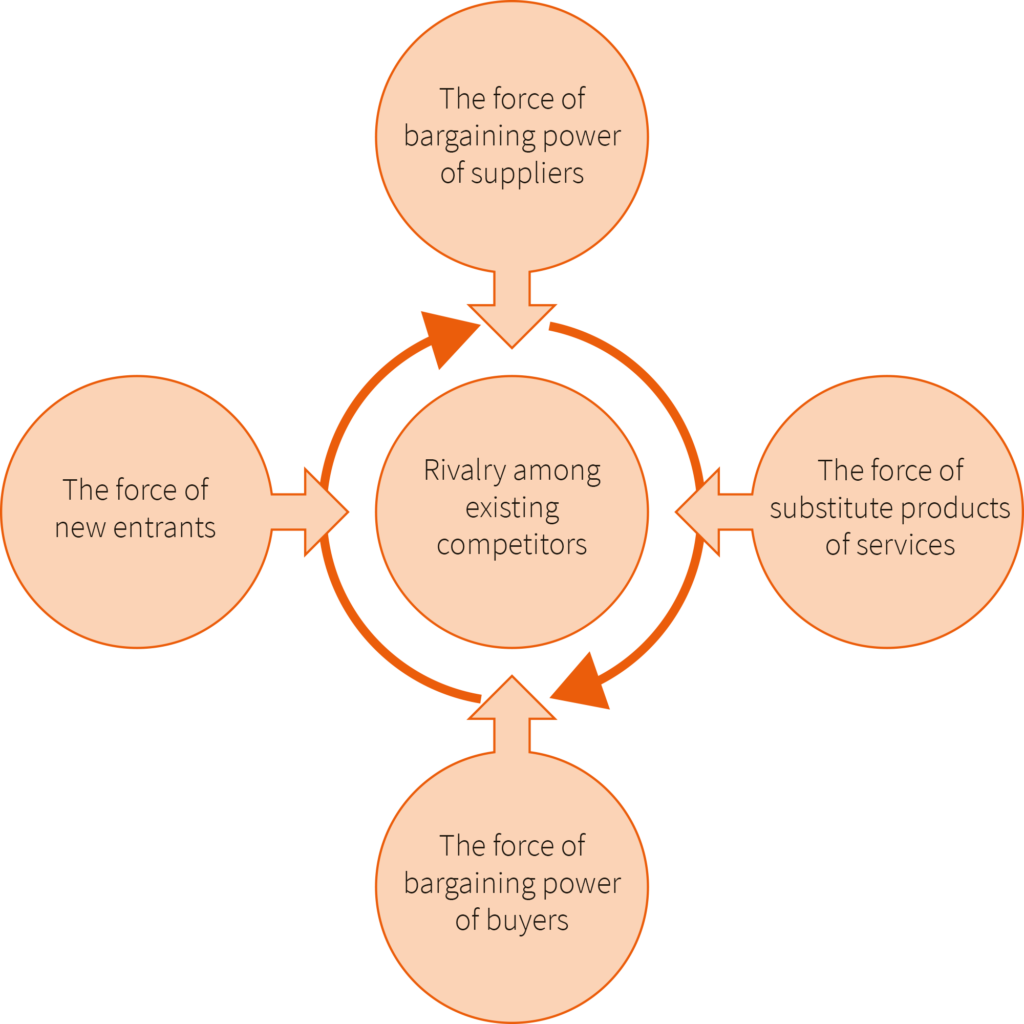

The questions within the survey were based on Michael Porter’s Five Forces analysis[2] Porter’s Five Forces are a commonly used tool to analyze how attractive an industry is. Porter distinguishes:

- Competition from rival sellers

- Competition from potential new entrants

- Competition from substitute products producers

- Supplier bargaining power

- Customer bargaining power

Porters Five Force Model

This model can be used as a frame of reference to examine numerous forces a security professional can address when establishing a “security strategy.”

In the survey, managers were asked whether the various forces they faced were dynamic or static in nature and whether the managers felt able to bend these forces to their strategic advantage. The results were used to compile a list of suggestions meant to help managers develop a more robust strategy[3].

The results were sobering. Two-thirds of the forces security managers said they face are dynamic. In other words, they are unpredictable factors such as intellectual property theft, extortion, hacking, social media rumors gone wild and other new-technology phenomena. Only one-third of the forces they deal with are static, such as compliance legislation, ISO standards and mandatory audits. Of respondents, 58 percent consider it important to address these external forces in their strategy formulation in the future. Since they had not done this up until the survey, the survey results show security managers focus their strategy on the more predictable, recurrent forces (compliance-related), rather than on the more plentiful and potentially more damaging forces.

Blind Spot

It is not as if security managers are naive. They are not. In response to the survey, in fact, they overwhelmingly indicated that supply chain risk management (e.g., cascade failures due to overlooked forces) should be one of the highest priorities in their organization. So, they understand they have a blind spot preventing them from anticipating risk. But knowing that is not enough. The survey showed that managers are poorly informed about the specific dangers they face and the potential impact of dynamic forces, much less about how they should respond in the event of a full-blown crisis. Of respondents, 78 percent said they poorly or fairly influence these forces once they impinge. An example of this can be seen through the April 2013 distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack that paralyzed ING Bank, a global financial institution based in The Netherlands. The incident slashed shareholder value and a flurry of criticism via social media cost ING customers[4]. If the bank had understood and respected the power of such dynamic forces—in this case, uncensored social media caused confusion[5]—and been transparent about the attack, the damage could have been limited. Instead, ING denied the seriousness of the attack, evaded questions and remained silent for far too long[6], allowing the conversation on Twitter to proliferate and leave the lasting impression that the bank had failed to respond. This incident, in addition to many others in current time (e.g. government institutes, hospitals, regular business), reveals a lack of preparedness—a gaping hole in the security strategy that is all too common.

Positive exceptions are observed now and then, at least in terms of crisis management. A good recent example is how the Dutch University of Maastricht responded when it was hacked in December 2019. Not only did they inform everybody about what happened, they also informed through the media how it happened and how it was resolved. Even the report giving insight in the cause but also in how it can be prevented was published after the hack. The university’s candid response profoundly influenced the tone of the ensuing (social) media debate, leading to more favorable public perception in the long term.

Containing vs. Averting Damage

Businesses need to develop an overall business strategy in which digital security is truly integrated, employing two of Michael Porter’s management frameworks: the Five Forces analysis[7] and the value chain. It has been shown how the Five Forces can be subdivided into dynamic and static forces and how inadequate security strategy is, with its inordinate focus on static forces. The second important concept that should be borrowed from Porter is the value chain. And here too, according to the survey findings, digital security misses the mark, typically focusing on individual activities of the organization rather than considering the role each activity plays in the wider picture. For instance, security specialists see that their business has relationships with third parties, but seldom recognizes these parties as potentially influential forces.

Understanding the value chain and the five forces is a prerequisite for business success[8]. Yet, surprisingly, Porter’s frameworks have yet to take hold in the digital security field.

The top five forces of which security managers say they recognize the impact are:

- Legislation—95 percent

- Inspection and supervisory agencies—88 percent

- Law enforcement (district attorney and police)—69 percent

- Partners in the (digital) chain (e.g., freight forwarders, Internet service providers, payment handlers)—64 percent

- Public opinion—60 percent

The top five forces of which security managers say they do not recognize the impact are:

1. Trade unions—79 percent

2. Social media (uncensored reporting)—57 percent

3. Criminals—48 percent

4. Customers—48 percent

5. Suppliers—43 percent

It is too easy to say that organizations simply need to get a grasp on the dynamic forces in the chain and all their problems will be solved. However, the problem is that very few management tools, steering mechanisms or key performance indicators (KPIs) are available to deal with these forces.

Dynamic forces can have major consequences. A surprising 71 percent of experts surveyed indicated that these forces are critical to their business and security strategy. They require the attention of every manager, board member and shareholder. This research shows that strategies based on an awareness of value chains and the five forces can help organizational leaders to:

- Heighten preparedness for unforeseen influences

- Better identify risk and establish the organization’s risk appetite

- Anticipate crises and remain in control of strategy

The top five elements for digital security strategy, according to the survey, are:

1. Stakeholder approach—When developing a strategy, involve the board of directors (BoD), management, business and all external stakeholders in the chain. Know the KPIs, stakeholder expectations, and how to translate these demands, using the right KPIs, into concrete benchmarks for the organization, management and BoD.

2. Risk-based approach—Look at the organization’s critical data security in the context of the entire chain. Start by gaining insight into all digital stakeholders and their potential dependencies, weaknesses and risk—both technologically and legally.

3. Beware the blind spot—Many forces are dynamic. Ensure the organization is not caught unaware. No one person can stay abreast of every development in this field, so let others update stakeholders on what they do not know.

4. Do the right things well—It may seem easier to “learn by doing,” but those who prepare a good strategy are less dependent on impromptu solutions.

5. Integrated organizational process—Be aware of the chain of forces that influences the organization. Make room for addressing these forces in the strategy and policy plans of the entire organization.

Case Study A strongly Internet-dependent Dutch business with an annual revenue of €500 million used these elements, Porter’s forces, to help it gain a better overview of its stakeholders. The organization realized that it had 266 percent more stakeholders than previously thought. By identifying all 166 digital stakeholders involved in critical business processes and their technical and/or legal dependencies, the organization was able to effectively map out and quantify all risk factors and feed this information back to process owners so risk management could be integrated throughout the organization. This made it easier to specify the knowledge and competencies needed to manage risk and to identify blind spots.

Conclusion

The message is simple: Each digital security leader needs to develop capabilities to zoom in on specific threats and prepare for them; zoom out and consider the entire context in which the organization operates. You need to “Detach”[9] yourself to get Situational Awareness and make the right decisions. The capability of zooming in and zooming out to identify potential (new) forces that might pose a digital risk is key. The capability of influencing those forces and take appropriate decisions is an important aspect of executing the strategy.

[1] Bobbert (2018) Improving the Maturity of Business Information Security On the Design and Engineering of a Business Information Security Artefact : https://www.managementboek.nl/boek/9789461263223/improving-the-maturity-of-business-information-security-yuri-bobbert

[2] Porter, M.; “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, 1979

[3] Porter, M.; “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance,” Free Press, 1985

[4] NOS, “Disruptions in Online Banking—377%,” 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/618846-storingen-online- bankieren-377.html

[5] RTL Nieuws, “Disruption at ING Caused Hours of Unclearness About Account Balances,” 3 April 2013, www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/storing-ing-urenlang- onduidelijkheid-over-saldos

[6] Van der Lans, Chantal; “Online Disruptions, Don’t Lose Your Customers’ Trust,” Usability.nl, 10 March 2014, www.usability.nl/2014/online-storingen-verlies-niet-het- vertrouwen-van-uw-klanten/

[7] Op cit, Porter, 1979

[8] McBeath, B.; “Supply Chain Orchestrator—Management of the Federated Business Model in This Second Decade,” 2010, www.clresearch.com

[9] Jocko Willing, Leadership Strategy and Tactics – Field Manual, 2020, First Platoon: Detach